Pioneering a New Frontier in Medicine

Philanthropy plays a vital role fueling breakthroughs in medical research.

“Our daughter is lucky to be alive,” says Marti of her daughter, Georgia. “And we were lucky to be in the hands of a team of pioneers.”

Indeed, the precocious 11-year-old is fortunate to have survived not just the initial impact of a devastating ATV accident, but also the grueling aftermath.

Vacationing in Montana, Georgia’s family booked an ATV tour their first day. Almost immediately, tragedy struck. The vehicle veered off course in a tunnel passage and flipped, pinning Georgia. Local doctors treated her for five broken ribs, a broken collar bone, severe bruising and contusions, and a concussion.

A few days later, though her bones were slowly healing, a serious problem remained. Georgia’s right lung was filled with fluid. Testing showed the fluid came from a source that remains mysterious to the vast majority of doctors—the lymphatic system.

As complex and important to overall health as the cardiovascular system, the workings of the lymphatic system have eluded medical science for generations. Much of that mystery stemmed from our basic inability to see the winding pathways and circuitous vessels that direct the flow of lymphatic fluid.

Thanks to the leadership of Yoav Dori, MD, PhD, cardiologist and Director of the Center for Lymphatic Imaging and Interventions at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), as well as early collaborators at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, all of that is changing. Dr. Dori and his team developed clinical imaging capabilities that shed light on this little-known system, enabling the delivery of more accurate diagnoses and more effective treatments. They’ve revealed an entirely new branch of medicine—and have now treated more than 250 patients who had nowhere else to turn.

“The experts told us Dr. Dori was the only person in the country who could handle Georgia’s condition.” Marti says. A medical flight to Philadelphia was quickly arranged. At CHOP, Dr. Dori used the advanced imaging technique he’d pioneered to show that the injury to Georgia’s collar bone had created a significant gash—right above her heart—that had torn her thoracic duct.

The team used a minimally invasive surgery they’d perfected to close the gash, stop the leak and allow Georgia to fully heal.

Georgia has since made a complete recovery. In fact, she competed in a horse show last June and recently had a starring role in her school’s production of Shrek.

“We are forever grateful for people who are able to think outside the box and come up with innovative treatments like this,” her family explains.

Driving Innovative Care through Philanthropy

But it’s not just brilliant physicians and innovative researchers who should be thanked for “miracle” treatments like the one that saved Georgia’s life. What few realize is the vital role philanthropy plays in fueling breakthroughs in medical research and advancing revolutionary new care models.

In fact, many hospitals rely on donor support to provide seed funding that can lead to “proof of concept” for projects that hold immense future promise.

Entities such as pharmaceutical companies and medical manufacturers—which sometimes fund work with clear commercial applications—generally decline to support research in its early stages, deeming such investment too risky. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) also rarely provide grants to fund novel theories.

Further, due to budget constraints, NIH funding for research declined by more than 22% between 2003 and 2015, representing a loss of nearly $10 billion in constant dollars. Today, funding remains 11% below its peak in 2003.

Compounding this decline, just 4% of NIH grants support pediatric medical research. Private charitable giving bridges that gap, providing a vital pathway from fledgling research to clinical care and empowering researchers’ efforts to develop new and innovative therapies.

Frankly, Dr. Dori’s work, and little Georgia’s recovery, might not have been possible without the support of visionary philanthropists such as the Chappell Culpeper Foundation.

John Chappell, a longtime resident of Malvern, serves as a board member for the foundation his daughter, Jennifer Paradis Behle, manages. Together they aim to create a permanent and positive shift in the trajectory of individuals’ lives through the support of education and healthcare.

Mr. Chappell and his family chose to support lymphatics research because of its novelty and what he describes as the obvious early success of Dr. Dori and his team to realize clinical benefits from their leading-edge research. The Chappell Culpeper Foundation’s investment helped underpin CHOP’s extraordinary efforts to unlock the mysteries of previously uncharted territory within us.

“We feel very fortunate to be involved in this invaluable work,” says Mr. Chappell.

Seeking Breakthroughs for the Tiniest Patients

Judy Barsema’s passion, on the other hand, took a different direction. Barsema, who lives in Kennett Square, was initially inspired to give to CHOP because she relished the opportunity to help children and families facing grave illness.

The mother of two and grandmother of five made her first gift to CHOP in 2008, and continued to support the general fund in modest increments for nearly a decade.

Then, she learned about CHOP’s innovative work to revolutionize care for extremely premature infants. Knowing that every dollar matters, she felt compelled to give more in support of this groundbreaking research.

Currently, of the one in 10 U.S. births that are premature, about 30,000 per year are critically preterm—younger than 26 weeks. Infants born near the limit of viability—at 22 to 26 weeks gestation—weigh as little as a bottle of water, and are so small they fit in a mother’s hand. Fewer than half survive.

Of those who do survive, 90% suffer sickness and disability, such as lung disease, cerebral palsy, blindness and brain damage. Surgeons and neonatologists at CHOP witness the effects of prematurity every day. Now, a team of them has innovated a system that could change the future for these vulnerable babies.

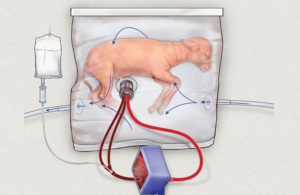

Alan W. Flake, MD, Director of the Center for Fetal Research in the Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment, and his colleagues have developed a revolutionary device that mimics the prenatal, fluid-filled environment of the womb, giving tiny newborns a few precious extra weeks to develop their lungs and other organs.

“Extremely premature infants have an urgent need for a bridge between the mother’s womb and the outside world,” says Dr. Flake. “If we can develop an extra-uterine system to support growth and organ maturation for only a few weeks, we can dramatically improve outcomes for extremely premature babies.”

The system they’ve pioneered mimics life in the uterus as closely as possible. There’s no external pump to drive circulation, because even gentle artificial pressure can fatally overload an underdeveloped heart. There’s no ventilator, because the immature lungs are not yet ready to do their work of breathing in atmospheric oxygen.

Instead, the baby’s heart pumps blood through the umbilical cord into the system’s low-resistance external oxygenator that exchanges oxygen and carbon dioxide, effectively substituting for the mother’s placenta.

The team has tested and monitored the new system on fetal lambs, whose prenatal lung development is very similar to humans’. If their results translate to clinical care, Dr. Flake envisions that in just a decade from now extremely premature infants will continue their development in comforting womb-like chambers filled with amniotic fluid rather than lying in incubators, attached to ventilators.

Besides significant health benefits, there could be a tremendous economic impact, reducing the estimated $43 billion annual medical costs of prematurity in the U.S.

“The idea of replicating the womb really caught my attention,” Ms. Barsema says of her contributions to fetal research. “Anyone who’s had a baby understands how special that system is. I am in awe of how far our doctors have come in that field and many other fields. It’s truly astounding.”

Revolutionizing Care for Deadly Cancers

At age 13, Mitch began to get sick frequently and to complain of pain in his legs. The pain became so intense that his parents took him to the emergency room at their local hospital in Spokane, Washington. He was diagnosed with an aggressive form of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Years of treatment followed, punctuated by disappointment after disappointment. In November of 2014, after Mitch’s second relapse, tests showed his leukemia had progressed into his brain.

His mom, Kari, remembers the day like it was yesterday. “His doctor said, ‘Mitchell, we can buy you some time, but there’s nothing else I can do for you.’”

“None of us were ready to be done fighting,” says Kari. “My husband Rob and I had read the story of the very first child who’d received immunotherapy at CHOP. So I picked up the phone.”

Chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy is a breakthrough treatment that genetically modifies a patient’s own immune cells to make them seek out and kill leukemia cells. The approach was developed in a collaboration between CHOP and a team led by Carl June, MD, a professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and Director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies in Penn’s Abramson Cancer Center. CHOP was the first institution to use the therapy in children with leukemia.

In a landmark decision in 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the revolutionary treatment—called Kymriah and now manufactured by Novartis—for children and young adults with treatment-resistant acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

For these kids, CAR-T cell therapy results in an 82% remission rate within three months after a single infusion, and 62% remain in remission for two or more years.

“Before this personalized, cellular gene therapy, these patients had about a 10% chance of surviving,” says Stephan Grupp, MD, PhD, Director of the Cancer Immunotherapy Program and Section Chief of Cell Therapy and Transplant at CHOP, and a Professor of Pediatrics in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “To see this 82% remission rate is beyond what we would ever have imagined.”

When Mitch and his family arrived in Philadelphia, Dr. Grupp met with them to discuss the procedure, explaining that the treatment had never been tried on anyone with the degree of brain leukemia Mitch had. Feeling it was worth the risk, Mitch then received his first dose of reengineered T cells.

The family had been warned Mitch might have a strong reaction to the treatment. As the T cells multiplied and attacked the leukemia, the affected areas, including his brain, became inflamed. Mitch soon spiked a fever, then began to experience neurological difficulties. He lay in a coma for five days.

On the fifth day, in the middle of the night, with Kari standing by his side and Rob at the foot of his bed, Mitch fluttered his eyes open and said, “Hi, Dad.”

Today, Mitch is in college, studying for a career in medical social work. He’s been cancer free for nearly four years.

This ultimate result may not have been possible were it not for years of investments in cancer research from individuals and families. Families like the Edwards who, tragically, lost their own son to brain cancer in 2002 at the age of 14.

Like Mitch, Stanley Edwards loved playing sports and spending time with friends. And, he dreamed of going to college one day. Stanley didn’t live long enough to fulfill his dream.

Determined to honor his legacy, his parents, Donna and Stan Edwards of West Chester, launched Stanley’s Dream through the Chester County Community Foundation to support cancer research, and to ensure that other children would have opportunities Stanley never did. They’ve supported neuro-oncology research at CHOP for the last 12 years.

“We are committed to helping other children and parents look forward to a brighter future.” says Donna. “We know, by giving back, we can make a difference.”

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was founded in 1855 as the nation’s first pediatric hospital. Through its commitment to providing exceptional patient care, training new generations of pediatric healthcare professionals and pioneering major research initiatives, CHOP has fostered discoveries benefiting children worldwide. Its pediatric research program is among the largest in the country and its family-centered care and public service programs have brought the hospital recognition as a leading advocate for children and adolescents. CHOP.edu