Juneteenth—National Freedom Day

Portraits Courtesy of Chester County Historical SocietyThe cause that has united freedom fighters continues today

What is Juneteenth?

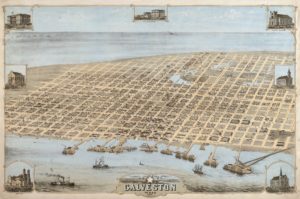

For over 150 years, there have been annual recognitions of the final announcement that slavery was ended in the United States. Celebrations first occurred when Union forces occupied Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865, which officially proclaimed freedom for all those still enslaved—more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Today official recognition of Juneteenth has spread to 47 states.

For over 150 years, there have been annual recognitions of the final announcement that slavery was ended in the United States. Celebrations first occurred when Union forces occupied Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865, which officially proclaimed freedom for all those still enslaved—more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Today official recognition of Juneteenth has spread to 47 states.

Specifically, Juneteenth is the anniversary date when 2,000 Union soldiers, under the command of General Gordon Granger, peacefully occupied Galveston, the last Confederate stronghold to surrender.

To ensure peace, General Granger issued various orders, including General Order No. 3, which stated in part, “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

Long Road to Equality

This order became a tipping point for the quest for equality. But it was not the first, nor last, to proclaim equality for all. For example, demands for abolishing slavery can be found in Pennsylvania as early as 1688 when a handful of German and Dutch Quakers led by Francis Daniel Pastorius produced the “Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery.”

While this was a start, Pennsylvania took nearly 100 years to become the first state to pass an abolition law. But even that didn’t immediately emancipate enslaved people in the Commonwealth. Instead, it allowed freedom only for future generations.

On the national level and beyond the military conflicts of the Civil War, it was Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 that set the course for official equality. Interestingly, that historic proclamation was not the first.

That honor would go to Navy Secretary Gideon Wells. In the summer of 1861, Wells found himself in charge of a navy with just a few dozen vessels, but war strategy required a fleet of 600 ships to effectively blockade Southern ports. He soon discovered there were not enough sailors to crew a larger fleet. However, enslaved people from border states, who were escaping to the Union in record numbers, made good workers aboard the ships. Others served as pilots and informants. All were motivated to lead the Union to victory.

But there was no legal premise for harboring these runaways. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, supported by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857, required runaway slaves to be returned to their owners. Even as the Civil War broke out, the Army reimbursed some owners for the loss of their so-called “property.”

Secretary Wells was undeterred. He needed sailors unimpeded by racist bureaucracy and in August 1861, he declared any runaway slave who made it to a ship or Navy Yard was to be considered “contraband.” They would then become employees of the Navy, receive a wage of $10 a month plus provisions, and be allowed to seek assignment aboard Union vessels with pay equal to their white crew members.

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation solidified the enslaved people’s new-found opportunity for freedom as public policy. By the end of the war, fully 20% of the Union Navy was made up of Black sailors.

Emancipation

After the war, Congress enacted three important changes to the Constitution—the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments—ending slavery, extending citizenship and providing voting rights to persons born or naturalized in the U.S.—including former enslaved people (but voting rights remained limited to men). These were essential steps to fulfilling the promise of emancipation.

While these amendments, ratified by the states during Reconstruction, gave African Americans new Constitutional protections, the struggle to achieve full equality continues to this day.

Juneteenth 2021

To continue the quest for freedom, community leaders have joined together to celebrate Juneteenth with several events (see sidebar). Partnering organizations initially included the Chester County Historic Preservation Network, Voices Underground, and Chester County History Center supported by the Chester County Board of Commissioners and Chester County Planning Department.

“We’re working together to create county-wide events to recognize and celebrate our rich heritage of embracing social justice and equality,” said Alexander Parham of Voices Underground, which is focused on elevating stories from the Underground Railroad. Other aspects of the celebrations will highlight the history of the Abolitionist movement.

Fighting for Freedom, an Ancestral Connection

The end of the Civil War has a special connection to my family. On May 24, 1865, my great-grandfather, John A. Johnstone, commanding the U.S.S. Cornubia off Galveston, fired the last shots of the war, sank the last Confederate warship, C.S.S. Le Compt, and captured the last Confederate Battle Flag that was passed on to Navy Secretary Gideon Wells.

The end of the Civil War has a special connection to my family. On May 24, 1865, my great-grandfather, John A. Johnstone, commanding the U.S.S. Cornubia off Galveston, fired the last shots of the war, sank the last Confederate warship, C.S.S. Le Compt, and captured the last Confederate Battle Flag that was passed on to Navy Secretary Gideon Wells.

This final chapter of the Civil War was achieved with an integrated crew that included 15 African American sailors, most of whom had been born into slavery. Official Naval records list each of their names and rank.

On June 5, 1865, two weeks before Juneteenth, Johnstone commanded the Cornubia, which became the flagship for Captain Benjamin Sands as it sailed into Galveston Bay to raise the Stars and Stripes at the Custom House and announce the final end of hostilities.

My great-grandfather and his valiant, diverse crew were there to celebrate.

*Read the entire story of my abolitionist great-grandparents at the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, CultureChesCo.org.

Malcolm Johnstone, Senior Program Officer for the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, is a frequent presenter and author of “For the Union, how Quaker abolition, a hanging, a slave riot, and a small newspaper in West Chester helped launch Abraham Lincoln’s quest for the presidency,” published by the Chester County Community Foundation. CultureChesco.org.

Juneteenth Celebrations

For 2021, the theme for Juneteenth celebrations is “Journeying Toward Freedom: Remembering the Past, Embracing the Present, Creating the Future.” Dozens of events have been planned throughout Chester County centered around the Underground Railroad and the abolition movement.

Find events sponsored by the following organizations, on their websites:

Voices Underground at VUProject.org

Chester County History Center at ChesterCoHistorical.org

Cultural Alliance of Chester County at CultureChesCo.org

Kennett Underground Railroad Center at KennettUndergroundRR.org

Event highlights include:

June 17. Town Tours & Village Walks Kickoff & Juneteenth Commemoration, June 17, at the Chester County History Center in West Chester (ChesterCoHistorical.org).

June 18–20. The headline events for the Juneteenth weekend

include national speakers and performers, as well as tours and several smaller events in the Kennett Square area, presented by local organizations that tell the story of the Underground Railroad (VUProject.org).

June 19. Underground Railroad Walking Tours, Saturday, June 19, created by the Chester County History Center in West Chester (ChesterCoHistorical.org).

Local Historic Heroes

Joseph J. Lewis (1801–1883)

A West Chester attorney and abolitionist, Lewis joined Thaddeus Stevens to defend Castner Hanway, a runaway slave who organized an uprising and killed his white owner in 1851 at what’s known as the Christiana Resistance. The legal team won an acquittal for Hanway, who eventually found his freedom in Canada.

Ann Preston (1813–1872)

The main speaker at the 1852 Pennsylvania Woman’s Rights Convention held at what’s known as Horticultural Hall in downtown West Chester, Preston was born and raised in Chester County and became one of the first women in the world to hold a formal medical degree.

Frederick Douglass (1817–1895)

He visited Chester County to recruit African American men for the Union military with his unwavering stance that “slavery should be utterly and forever abolished in the United States.” A statue of Douglass stands on the West Chester University campus.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823–1893)

An African American activist, writer, teacher and lawyer, Cary lived for a time in West Chester with her family. At the age of 16, she started one of the first schools for African American children in Westtown.

Charlie King (1849–1862)

Born and raised in West Chester, King served as a drummer boy in the Union Army at the age of 13. In September 1862 at the Battle of Antietam, he was killed by artillery fire, the youngest soldier killed in action during the Civil War.

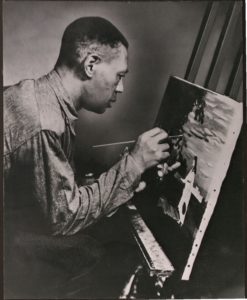

Horace Pippin (1888–1946)

Born in West Chester and returning in adulthood, Pippin was one of the most original artists of his generation, with paintings in the collections of the Barnes Foundation and Phila. Museum of Art. A World War I veteran and self-taught artist, his most expressive works address America’s history of slavery and racial segregation.

Born in West Chester and returning in adulthood, Pippin was one of the most original artists of his generation, with paintings in the collections of the Barnes Foundation and Phila. Museum of Art. A World War I veteran and self-taught artist, his most expressive works address America’s history of slavery and racial segregation.

Bayard Rustin (1912–1987)

Born in West Chester, Rustin organized equality rallies early in his life. He’s most famous for his role as chief organizer of the March on Washington in August 1963, where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech.

Our Favorite Resources

- Berk Hathaway Holly Gross

- Berk Hathaway Country Prop

- Chester Cty Community Fdn

- Chester Cty Hosp, Penn Med

- Chester Cty Library System

- Colonial Theatre

- Delaware Museum of Nat & Sci

- Key Financial, Inc.

- King Construction

- Mercedes Benz

- Osher Lifelong Learning

- Ron’s Original

- Tim Vaughan

- West Chester BID

- Walter J. Cook