Four Women Who Made History in Chester County

A small sample of an important group

March is Women’s History Month, and there’s no better time to learn more about our foremothers. Let’s start by focusing on four with ties to Chester County.

It’s a sad fact of history that women have faced many barriers, especially those created by sexism and, among women of color, racism. But among all those who struggled, there are four whose perseverance and integrity distinguished them and made them champions of their age.

Here’s an introduction to their stories to inspire you.

Women Iron Master

Rebecca Lukens (1794–1854), Coatesville

As the oldest of seven children, Rebecca Lukens learned what it took to run an iron mill on the coattails of her father, an iron master busily running an early ironworks in the Brandywine Valley. Rebecca had no idea that as a young woman she would step into the job of iron master herself and build the largest ironworks in the country in present-day Coatesville.

Rebecca began on this path when she was a young mother and wife setting up house with her husband, Charles Lukens. Charles had taken over the ownership of Brandywine Steel and made it the first in the United States to mill rolling boiler plates.

Then in June of 1825, tragedy struck when Rebecca’s husband died after a brief illness, leaving her with three daughters and a fourth on the way. To add to her stress, she had made a final promise to Charles that she would carry on with the management of the iron mill despite it being deeply in debt.

It took nine years, but her perseverance and skill finally made the company profitable, and she never laid off a single worker. All this was accomplished in a business world ruled exclusively by men.

In 1859, the company was renamed Lukens Ironworks in her honor.

The First Telecommuter

Emma A. Hunter (1831–1904), West Chester

In 1851, Emma Hunter (later Smith, her married name), at the age of 19, was among the first female telegraph operators in the world. At that time, the Atlantic & Ohio Telegraph Co., an enterprise that was laying lines for a nationwide telegraph system, included West Chester as part of that early electronic internet.

In 1851, Emma Hunter (later Smith, her married name), at the age of 19, was among the first female telegraph operators in the world. At that time, the Atlantic & Ohio Telegraph Co., an enterprise that was laying lines for a nationwide telegraph system, included West Chester as part of that early electronic internet.

Emma, who lived with her widowed mother and younger brother, had opened a small stationery store at their home on Church Street in West Chester. Running such a shop helped the teenager gain both business and writing skills. But it was a meager living, and she was anxious for a better job.

An opportunity came her way when the new telegraph company needed an operator for their West Chester location. Emma quickly applied herself to learning the new skills and soon demonstrated the highest aptitude for Morse code — the language of the telegraph. Emma not only got the job, she negotiated to have the company install wires directly to her home, where she then set up the first local telegraph office.

With that, Emma became the first female in the brotherhood of telegraph operators, and she insisted proper decorum towards her be kept at all times. This helped set high standards as more women entered the workforce.

Women’s Rights Advocate

Ann Preston, M.D. (1813–1872), West Grove

Ann Preston could have taken an easier path in life and been content to celebrate her many accomplishments. Dr. Preston graduated first in her class from the newly opened Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1851. She went on to enjoy a successful medical practice focusing on women’s health and was elected Dean of the Medical College in 1865, the first woman in America hold such an office. In addition, she became an author of a popular book of children’s poems called “Cousin Ann’s Stories,” which became a 19th-century classic.

Ann Preston could have taken an easier path in life and been content to celebrate her many accomplishments. Dr. Preston graduated first in her class from the newly opened Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1851. She went on to enjoy a successful medical practice focusing on women’s health and was elected Dean of the Medical College in 1865, the first woman in America hold such an office. In addition, she became an author of a popular book of children’s poems called “Cousin Ann’s Stories,” which became a 19th-century classic.

But Dr. Preston wanted to do more to support all women and find ways to ensure women enjoyed the same rights that were, in her lifetime, provided only to white men. To make an impact, she organized the first Women’s Rights Convention in Pennsylvania (the second in the U.S.) at Horticultural Hall in West Chester in June 1852, which attracted women’s rights activists from around the country. A high point of the convention was the keynote speech Dr. Preston gave to develop resolutions addressing women’s suffrage, equal pay and equal access to education.

Her spirit and leadership skills continue to act as an inspiration for everyone seeking equal rights.

Woman of Action

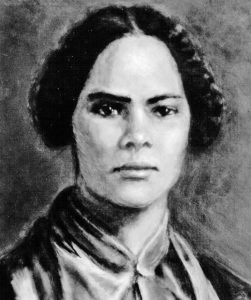

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823–1893), West Chester

When 10-year-old Mary Ann and her family moved to West Chester in 1833, her parents made sure she received an education. As a young teenager, Mary Ann quickly discovered that schooling for Black children was very limited. She then took it upon herself to teach children of color who were not allowed to attend public schools. These efforts allowed her to open a school in West Chester for Black children in 1840, followed by another school in Wilmington, Delaware.

When 10-year-old Mary Ann and her family moved to West Chester in 1833, her parents made sure she received an education. As a young teenager, Mary Ann quickly discovered that schooling for Black children was very limited. She then took it upon herself to teach children of color who were not allowed to attend public schools. These efforts allowed her to open a school in West Chester for Black children in 1840, followed by another school in Wilmington, Delaware.

Mary Ann’s activism took a significant step when famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass asked readers of his publication, The North Star, for suggestions on improving the lives of African Americans. Mary Ann promptly wrote a letter to Douglass with the phrase that “we should do more and talk less.” The letter impressed Douglass and was reprinted and circulated.

Mary Ann also helped define a new role for Black women by encouraging her community to abandon the “separate but equal” position of white abolitionists and demanding full integration of African Americans. Her legacy continues to inspire the equal rights movement of today.

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer with the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation.

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer with the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation.

Many thanks to the Chester County History Center Library for providing access to research material.