Beyond Bird Banding

Cover Photo by Blake GollUsing new technology to study migratory birds to help reverse their loss

It’s spring! Across the globe millions of migratory birds are readying themselves for the transcontinental trip of a lifetime.

Every year around this time people fill their bird feeders and eagerly await the return of many beloved species to their backyards. Dog-eared copies of favorite field guides and digital tools, like eBird and BirdCast, can help folks anticipate the movements and arrival of these seasonal visitors.

Yet these tools don’t tell the full story.

A sad chapter includes a study published in 2019 that revealed North American bird populations have declined by 29% across all species since 1970. That’s close to 3 billion birds lost! While certain birds, like ducks and woodpeckers, have increased—thanks to targeted conservation efforts—others including Eastern meadowlarks, barn swallows and even many common songbirds like Baltimore orioles, are all declining.

Using newer technologies combined with traditional methods, researchers have been able to gain insight into these losses. Conservation organizations throughout the Mid-Atlantic, led in part by teams based in Pennsylvania, are following a global model for research collaboration that can shed light on these losses and move more people to action to save habitat for wildlife and humankind alike.

Studying Migratory Birds

One of the longest-lived tools researchers use to aid the study of birds is banding. Banding involves capturing wild birds, attaching uniquely numbered bands around the bird’s leg, and then releasing the bird back into the environment.

These bands help identify the birds so they can be tracked by researchers throughout the animal’s lifespan.

Many species return to the same breeding grounds year after year. However, migratory birds rarely return to the exact site and less than 1% of banded birds are captured again, making banding less effective.

So what happens when birds fly the coop? That’s where newer technologies like radio telemetry can greatly increase understanding of what’s happening to our birds and other animals while they are abroad.

Using Radio Telemetry

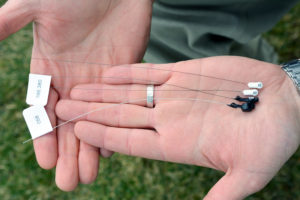

Radio telemetry works by outfitting a bird or other animal with a small radio transmitter mounted on a removable harness. When the animal moves through areas with antennae and receivers on the appropriate frequency, it can be tracked by its transmitter’s signal.

Researchers studying animals in designated locations like preserves can use handheld antennas and locate their specimens while on foot. This can be limiting when working with migratory wildlife that spend parts of their life in completely different areas of the world.

Enter the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international network designed to track flying migratory wildlife throughout the world.

Using Motus

The Motus Wildlife Tracking System (Motus) is an international collaborative research network established by Birds Canada. The network uses automated radio telemetry to track migratory animals as they move seasonally across the globe.

Instead of tracking animals on foot, researchers let strategically placed stationary receivers do the work. Using Motus, a researcher can see where a bird goes after it’s left the breeding grounds and track it across hundreds or even thousands of miles!

Seeing Motus’ potential to help improve the efforts of individual researchers, Willistown Conservation Trust’s Bird Conservation Program teamed up with collaborators from Project Owlnet, the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art, and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, then developed a plan to set up receiving stations throughout Pennsylvania and the Mid-Atlantic.

This team of field technicians, researchers, educators and project managers—known as the Northeast Motus Collaboration—have installed 85 receiving stations to date in the Mid-Atlantic alone. Increased participation in the network across the Americas, Europe and Australia has helped increase Motus’ overall “listenership” from 350 stations in 2017 to just over 1,000 today.

Learning from Motus

More than 230 species of birds have been tagged and more than 120 publications have been made possible from this data since the Motus network was established. Researchers are discovering many things from the data—from the effects of commercial insecticides on migratory songbirds and monarch butterflies, to how body condition affects the speed of migration, to the secret nightlife of birds!

While working with Willistown Conservation Trust’s Bird Conservation Program in 2020, I began working with educational materials created by educators from Birds Canada to develop lessons around species of greatest conservation need in Pennsylvania. One such species is the wood thrush, which breeds in forests and wood lots throughout the Eastern U.S. and Southeastern Canada.

The Motus network has also allowed me to host workshops to connect educators who are eager to use real-world research in their programs and to help the public connect to birds on a more personal level.

By sharing Motus’ database and educational resources and exploring how to integrate existing programming from organizations like Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Birds Canada, educators can create valuable learning experiences for youth and adults alike. Programs like Project FeederWatch encourage observation of both resident and migratory birds right at home, which can be the spark to ignite further learning around migration and species of interest to the Motus network.

Doing More to Help

Collaborating with the Motus network is one way to help promote conservation, but there are many things each of us can do at home and in our communities to educate ourselves and others about the challenges facing birds worldwide. See the sidebar.

Willistown Conservation Trust’s conserved land includes three nature preserves open to the public year round, free of charge. These preserves have scenic walking trails and abundant wildlife. Visit WCTrust.org/birds for information about the Bird Conservation Program’s work and NortheastMotus.com to learn more about the Mid-Atlantic Motus network.

Ways You Can Help

Resources from the 3 Billion Birds campaign (3BillionBirds.org) offer concrete ideas to help slow the decline of the bird population. Some things that can help stem critical losses of wildlife include simple steps like:

- keeping domestic cats indoors,

- monitoring and helping reduce window collisions,

- planting native plants,

- decreasing pesticide use,

- drinking bird-friendly coffee,

- reducing reliance on plastics, and

- watching and recording observations of wild birds.

You may also want to explore migration data at Motus.org/Explore-data.

Or check out Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s “Seven Simple Actions to Help Birds” at Birds.Cornell.edu.

For even more, read “A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds,” a new book by PA-based naturalist Scott Weidendaul.

Learn more at NortheastMotus.com.