Pressed Plants: Bringing the Outside in with Botanical Crafts

Photos courtesy of Jenkins Arboretum & GardensKeep the tradition from fading away

The beauty of a spreading sugar maple, a bank of phlox in full bloom or a clump of arching ferns has few rivals. Native plants are enjoyed to the fullest when grown in your own garden, yet slipping a bit of their loveliness into the rest of your life — from your kitchen decor to your quiet reading time — is simple. Through the art of botanical pressings, your favorite native plants can grace every hour of the day. All that’s required is scrap paper, a couple of heavy books and patience.

The beauty of a spreading sugar maple, a bank of phlox in full bloom or a clump of arching ferns has few rivals. Native plants are enjoyed to the fullest when grown in your own garden, yet slipping a bit of their loveliness into the rest of your life — from your kitchen decor to your quiet reading time — is simple. Through the art of botanical pressings, your favorite native plants can grace every hour of the day. All that’s required is scrap paper, a couple of heavy books and patience.

Tradition

Pressing and drying flowers to preserve them has engaged people for centuries, since some of the earliest human civilizations. After European travelers were impressed by the Japanese practice of Oshibana (which used pressed plant material as the medium for stunning artwork), pressing became a popular pastime for women of the Victorian era. Not only did it encourage creative expression, plant pressing also enabled women to practice botany during a time that considered science a masculine pursuit.

Even Emily Dickinson, perhaps best known for her poetry, pressed plants to create an herbarium that demonstrated both scientific meticulousness and attentive artistry. Botanists also made pressings to exhibit the species they discovered on research trips.

Today, pressed plants continue to play roles in both science and art, from inspiring clothing designs to preserving the genetic information of endangered plants.

Although any plant can be a candidate for pressing, preserving portions of native species this way is extra special. The process of collecting and drying flowers, leaves and stems might cause you to notice details that escaped you before, such as the fine fuzz on new oak leaves or the subtle color variations on coneflower petals. If you press plants in multiple seasons, you’ll begin to develop an intimate acquaintance with the schedule of our local flora, noticing when the sugar maples leaf out or the asters finish blooming.

Crafting with your dried collections can reveal unexpected beauty in the shapes of leaves or the color tones of grasses. Ready to join the tradition?

Collect

Take a sharp pair of scissors, a small basket to hold your findings and an open mind, and head out into a space where you have express permission to gather — such as your own garden! Herbaceous flowers, leaves and stems can be gently snipped from their plant (as if you’re harvesting culinary herbs). Take only as much as you can press in about 30 minutes — more will just wilt and be wasted. And follow the one-in-ten rule — for every one flower or leaf you take, leave at least ten behind to ensure the sources of your pressings continue to thrive.

Take a sharp pair of scissors, a small basket to hold your findings and an open mind, and head out into a space where you have express permission to gather — such as your own garden! Herbaceous flowers, leaves and stems can be gently snipped from their plant (as if you’re harvesting culinary herbs). Take only as much as you can press in about 30 minutes — more will just wilt and be wasted. And follow the one-in-ten rule — for every one flower or leaf you take, leave at least ten behind to ensure the sources of your pressings continue to thrive.

Beyond these precautions to be a responsible artist, the types of plant material you can press are as wide as your curiosity and attentiveness. Still, certain textures and shapes have more predictable results than others. Here are a few tips to help you get started.

Flat pieces dry readily and keep their shape. Leaves in particular look very similar pressed and fresh, and many outlines that get lost in the woodland masses are truly wonderful in artwork.

For example, sugar maple (Acer saccharum) has delicate points that are particularly lovely on tiny, young leaves. Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) and violet (Viola spp.) are heart shaped. Ferns have marvelous lacy forms that often repeat themselves in miniature upon each frond, so a single frond can be divided into many tiny ferns.

For example, sugar maple (Acer saccharum) has delicate points that are particularly lovely on tiny, young leaves. Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) and violet (Viola spp.) are heart shaped. Ferns have marvelous lacy forms that often repeat themselves in miniature upon each frond, so a single frond can be divided into many tiny ferns.

Fragile petals, such as those of garden phlox (Phlox paniculata), often stick to the paper they’re pressed on. Leaving the flower attached to its stem and permitting it to dry folded on its side rather than flat makes the whole piece sturdier and can create more interesting results than the flowers alone. Other native plants that press beautifully as composites of flower, stem and leaf include sweet pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia), ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis) and hairy alumroot (Heuchera villosa).

Thick or fleshy plant material is best avoided, but individual petals often make great pressings where whole flowers are impossible. Prime petal-pressing prospects include purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), black-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia spp.) and tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera).

Capture

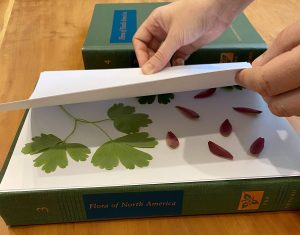

Preserving your basketful of plant material as quickly as possible increases the quality of the dried results. Start by laying a few sheets of clean, blank paper (avoid colored print) on the cover of a heavy book. Over this, place a single layer of whole flowers, single petals, grasses or leaves. Make sure none of these materials are touching each other and they’re broken into the sizes you’d like them to be in the final product.

Preserving your basketful of plant material as quickly as possible increases the quality of the dried results. Start by laying a few sheets of clean, blank paper (avoid colored print) on the cover of a heavy book. Over this, place a single layer of whole flowers, single petals, grasses or leaves. Make sure none of these materials are touching each other and they’re broken into the sizes you’d like them to be in the final product.

Once you’ve filled the paper, lay two or three more sheets of paper on top of the plants, taking care not to shift them around too much. You can place another layer of plants in the same way upon this paper. When you’ve used all your plant material, top it all off with a few more sheets of paper and another heavy book. Set the whole plant press somewhere it will remain undisturbed, preferably in a warm, well-ventilated room.

You have some time to plan what you’ll do with your pressings.

You have some time to plan what you’ll do with your pressings.

After two or three weeks, lift the top book and the first sheets of paper to check on your pressings. If they feel crisp, fragile and papery, they’re fully dried. Gently remove each from the paper and slip them into an envelope to store them. Keep them out of sunlight and many flowers and leaves retain their color for years.

Create

Botanical pressings can be affixed to any flat surface with diluted white, nontoxic glue. Spread the glue over the backs of the pressed plants with a small paintbrush and smooth them down where you want them. After the glue has dried, protect the completed artwork with laminate or a clear protective sealant, such as polycrylic finish.

Botanical pressings can be affixed to any flat surface with diluted white, nontoxic glue. Spread the glue over the backs of the pressed plants with a small paintbrush and smooth them down where you want them. After the glue has dried, protect the completed artwork with laminate or a clear protective sealant, such as polycrylic finish.

Excellent objects to start decorating with your dried flowers and leaves include bookmarks (cut from cardstock), journals, electrical outlet covers, coasters and lampshades.

Your imagination is the limit!

Jenkins Arboretum & Gardens is a 48-acre public garden showcasing native flora of the eastern United States and a world-class collection of rhododendrons and azaleas. The gardens are open every day of the year and admission is always free. Plan your visit by visiting Jenkins online at JenkinsArboretum.org.

Our Favorite Resources

- Arrowwood Landscape Design

- B&D Builders

- Ball & Ball

- Berk Hathaway Country Prop

- Berk Hathaway Holly Gross

- Berk Hathaway Missy Schwartz

- Cullen Construction

- Dayton Lock

- Dewson Construction

- E.C. Trethewey

- Homestead Structures

- Keystone Gun-Krete

- King Construction

- Main Street Cabinet Co.

- McComsey Builders

- Monument/Sotheby’s Int’l

- Mostardi Nursery

- Mountaintop Construction

- MR Roofing

- NV Homes

- Precise Buildings, LLC

- Rittenhouse Builders

- Sheller Energy

- Shreiner Tree Care

- Stable Hollow Construction

- Warren Claytor Architects

- Wedgewood Gardens

- White Horse Construction