Brandywine Stories: Bayard Rustin, A Renaissance Man

An activist with a local connection

If you didn’t already know about Bayard Rustin (1912–1987), it’s time. Rustin’s story has been getting some much-deserved attention recently after being almost written out of history books because of his early association with the Communist Party and his homosexuality.

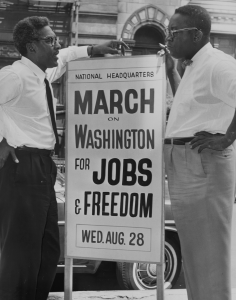

The November 2023 premiere of the Netflix movie Rustin, produced by Barack and Michelle Obama, brings Rustin’s story of integrity and bravery to life as he waged battles on many fronts: organizing the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, working for social justice, nonviolence and gay rights, among other causes. The film attracted additional attention after its Oscar nomination for Best Actor for Philadelphia-born Colman Domingo, who starred as Rustin, and who also received an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Actor.

Early Years in West Chester

Born in West Chester, Rustin was raised by his grandparents, who were well-to-do local caterers. His grandmother Julia was a Quaker and a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Rustin attended local segregated grammar schools, where he excelled academically and was encouraged by teachers to develop leadership skills he’d use throughout his life.

In his teenage years, Rustin lived just across the street from the artist and abolitionist Horace Pippin. We can only imagine what impact the successful Black artist’s life and career had on the budding activist.

Rustin graduated from West Chester High School in 1932. The school was not officially segregated because there were not enough Black students for a separate school. Yet while traveling as a member of the school’s football team, Rustin encountered discrimination when he was refused service at a restaurant in Media.

In 1968, the school was renamed Henderson High School, and Rustin was recognized for his social justice work by being the first person in the school’s Hall of Fame. In 1995, the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission honored him with an outdoor historical marker placed at Lincoln and Montgomery Avenues, on the grounds of the high school.

Influences

Rustin embraced and was trained in the Quaker ethic of nonviolence and pacifism. He insisted those who joined him in protests would never respond in a violent fashion, even when attacked. One of his first organized demonstrations was to protest segregation at the Warner Theater, a West Chester movie house where Black patrons were restricted to the balcony so they wouldn’t be seen.

Legend has it that when a young white woman wanted to join Rustin and other Black protesters, he politely refused, fearing for her safety. Although there were no reports of violence, the event resulted in Rustin’s first arrest. The Warner Theater is gone, but the structure still stands on North High Street. The indoor staircase that Black patrons used is the only hint of that shameful time.

Rustin continued to demonstrate at segregated places such as the Woolworth’s lunch counter and YMCA. These actions sparked the development of what’s now the Melton Center on East Market Street in West Chester. The surrounding neighborhood worked hard to ensure it met the needs of Black families, eventually building a theater, banquet room, basketball court and swimming pool.

Early activism also included membership in the Communist Party USA because of their support of civil rights for African Americans and later the Socialist Party, working on behalf of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Rustin’s other wide-ranging efforts included protecting the property of Japanese Americans imprisoned in internment camps during World War II, working to integrate interstate bus travel as a Freedom Rider, and aiding refugees from Vietnam and Cambodia.

Musical Talent

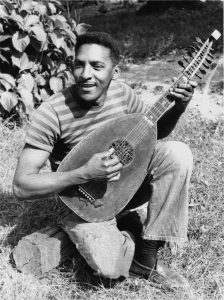

A lesser known but important ability was Rustin’s musical talent, using the power of song to transform and inspire civil rights demonstrators and calm hostile agitators. He’d often accompany himself on mandolin, guitar or, surprisingly, the lute. Viewers of the Rustin movie may recall a brief scene showing him playing his lute.

In fact, as a young man, Rustin considered becoming a professional singer and actor, a common path among abolitionists. For example, Justin Holland (1819–1887), a friend and supporter of Fredrick Douglass, both participated in the Underground Railroad and became a champion of American classical guitar by publishing over 300 arrangements and compositions for guitar.

An accomplished tenor vocalist, Rustin’s talent helped earn him scholarships to both Wilberforce University and Cheyney State Teachers College. In 1939, he went to New York and sang in the chorus of the short-lived Broadway musical John Henry, which starred Paul Robeson.

Rustin’s interest in old instruments grew when he received a lute as a gift during his sentence in federal prison from 1944–46 for refusing to serve in the armed forces. (While in prison, he organized protests against segregated housing and dining.) Rustin then had the time and talent to teach himself how to play the instrument, and by 1952 became proficient enough to complete an album called Elizabethan Songs and Negro Spirituals.

If you weren’t familiar with our local activist, Juneteenth is an apt time to remember Rustin’s legacy. This newest of national holidays, which celebrates social justice, traces back to June of 1865, the end of slavery in the U.S. It connects with Rustin’s work on the March on Washington that set the stage for Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech to a peaceful crowd of 250,000.

Overdue Acclaim

On August 8, 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian award. During the presentation, President Obama stated: “Bayard Rustin was an unyielding activist for civil rights, dignity and equality for all.” Walter Naegle, Rustin’s same-sex partner, accepted the award.

That same year, Cheyney University honored Rustin with a posthumous Doctor of Humane Letters degree at its commencement, and almost 30 years earlier, in 1985, Haverford College awarded Rustin an honorary doctorate in law.

In a different kind of honor, Rustin was the subject of a full-length play, Bayard Rustin Inside Ashland, dramatizing his World War II prison experience and its role in his activism. The play had its world premiere in May 2022 at People’s Light in Malvern.

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer for Arts, Culture and Historic Preservation for the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation. His column raises awareness of Chester County’s rich heritage as we journey to 2026: the year the U.S. celebrates the 250th anniversary of our nation’s independence.

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer for Arts, Culture and Historic Preservation for the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation. His column raises awareness of Chester County’s rich heritage as we journey to 2026: the year the U.S. celebrates the 250th anniversary of our nation’s independence.