Mammography: What’s a Woman To Do?

In the world of medical advances, it’s difficult for patients to keep up. Especially when research in the news gives two different results, and the medical community says it’s not clear what to do. Plus, it doesn’t help to have multiple medical guidelines that conflict—guidelines are supposed to embody consensus in the medical community about best practices, to guide patients on what to do. This confusion is certainly true for mammograms.

Conflicting Guidelines

Conflicting Guidelines

To understand where we are on mammogram guidelines, it’s important to know how we got here. Let’s start with the mammogram screening guidelines published in 2009 by the U. S. Public Services Task Force (USPSTF)—a government agency of volunteer clinicians and epidemiologists with expertise in information technology, pediatrics, epidemiology, cardiovascular diseases, obstetrics and other areas, but not including expertise in breast diseases.

These guidelines were highly controversial because they included new recommendations to stop performing mammograms for women of average risk aged 40 to 49, but to wait until age 50, and then do screenings every other year. The new recommendation noted mammography did save some lives in women 40 to 49, but it saved fewer lives in those under 50, and the task force believed the resulting disadvantages outweighed the benefits.

This set off a firestorm of objections.

In addition, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required coverage only of mammograms recommended by the USPSTF (and three other specified committees) that were at a high level of evidence, which excluded women 40 to 49.

Concern mounted that these changed recommendations, and the ACA rules, might result in insurers no longer covering mammography for women aged 40 to 49. Concerns for safety were so great and objections so widespread by breast experts, clinicians, medical societies and patient advocacy groups, that bipartisan legislation was passed later that year requiring insurance coverage for mammography for women 40 to 49.

Meanwhile, the American Cancer Society disagreed with the USPSTF recommendations, but also opposed the new legislation because it interfered in the USPSTF’s role.

At this point, except for the USPSTF, there was broad consensus that mammography should be performed annually beginning at age 40 and not stopped until a patient and her doctor felt abnormal findings would not be acted on. If, for example, the patient were too sick to treat something found on a mammogram, there was no point in doing one.

Our Current Situation

Jump now to 2015. The American Cancer Society put out its own recommendations for screening women of average risk, causing more controversy and confusion. These guidelines specified women 45 to 54 should get mammograms every year, and women 55 and older should get them every other year, until their expected lifespan was 10 years. But, the guidelines emphasized that women 40 to 44 should have the option to begin mammograms, and if women 55 and older wish to do annual mammography, they should also have the option to do so.

Confusion ensued, further fueled by an updated set of USPSTF guidelines. USPSTF’s updated guidelines were essentially the same as in 2009, but now were more carefully worded. Controversy remained, but probably because of the ongoing public discussion, did not get as much attention.

Next, the American Society of Breast Surgeons diverged from other medical groups to put out its own guidelines, making recommendations that straddled the two approaches.

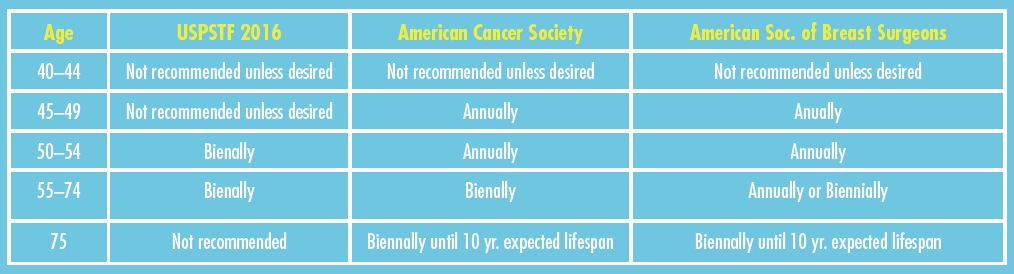

So, this is what we have:

And yet, despite this history, many medical societies, like the American College of Radiology, still recommend annual screening mammograms from age 40 onward.

So What’s a Woman To Do?

The short answer is to speak with your doctor, and specifically, find yourself a clinician who treats nothing but breast disease and is knowledgeable about the field and the studies. The reason for the controversy is that the published research, while very extensive, has varied conclusions and can be interpreted in different ways when the data from the studies are looked at in detail apart from the researcher’s own conclusions. This is where a knowledgeable breast specialist is invaluable.

My personal recommendation to patients is still to begin mammograms annually at age 40 for those at average risk and considering medical history, and continue until the patient feels she wouldn’t act on findings because of either personal desires or her health. I also recommend regular self-examination. This course of action has been the desire of my patients.

Yet, the varied recommendations above suggest that an individual’s concerns and preferences do leave room for variation. The disadvantages of starting later or varying the timing of mammograms may not be as great as previously thought.

Beyond the Basic Mammogram

The other thing the guidelines recommended, that I agree with, is that medical research has not identified any specific group of women who benefit from tomosynthesis (“3D mammography”). So, right now, we don’t know who should get this type of mammogram rather than standard digital mammography. It may benefit women with dense breasts, but trials are not complete and that remains uncertain.

Also, MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) are not recommended for routine use, and have been shown in numerous studies to have significant disadvantages and little benefit when used routinely in women of average risk.

Bottom Line

Talk to your breast specialist. While most still suggest annual mammography beginning at 40, there’s still a lot of discussion. Besides, one conversation with your clinician may be a whole lot easier than trying to sort through the confusion yourself.

Here’s a helpful chart for quick reference:

Richard J. Bleicher, M.D., F.A.C.S., is the Breast Clinical Program Leader and Associate Professor of Surgical Oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. A graduate of Temple Medical School, he did his residency at Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh and a surgical oncology fellowship at John Wayne Cancer Institute, Santa Monica.

Richard J. Bleicher, M.D., F.A.C.S., is the Breast Clinical Program Leader and Associate Professor of Surgical Oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. A graduate of Temple Medical School, he did his residency at Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh and a surgical oncology fellowship at John Wayne Cancer Institute, Santa Monica.