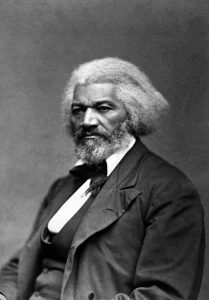

Brandywine Stories: The Final Words of Frederick Douglass

And a lasting tribute in West Chester

At the end of January 1895, the 78-year-old Frederick Douglass made his way to West Chester. It had been more than 40 years since his last visit, and he viewed this as an opportunity to become reacquainted with old friends and supporters. The group reminisced about the days when Douglass would address crowds in downtown locations and recruit local Black men to join the Union Army in the name of freedom.

Douglass’s current visit resulted from an invitation from West Chester State School (now West Chester University). The school wanted the venerable freedom fighter to give a speech for students and residents alike on February 1. Douglass agreed to a small fee, updated his notes for the occasion, and met with the supportive audience at a comfortable hall on campus.

After his introduction, Douglass approached the lectern to enthusiastic applause. He began by sharing the many pleasant memories of his previous visits. He remembered those he’d met as refined and intelligent, but it was the hospitality of the Darlington family he was most fond of, because they’d given him their home during this visit.

Douglass then shifted to the core of his lecture by reading from his notes “in a low and subdued tone,” reported the Daily Local. Clearly, old age was taking its toll, as Douglass appeared bent and frail, although it was noted there were “occasional suggestions of the fire which warmed his heart and made him a powerful foe of anti-slavery.”

Indeed, he would often step away from the lectern and then speak with eloquence about his most adamant positions. This reminded many of the older listeners of Douglass’s younger days when he could move an audience to actively support the cause of freedom for all.

Lynch Mobs

For this speech, Douglass was embracing a new challenge of terror that was sweeping the United States: lynch mobs. In April 1894, a periodical called The Christian Educator published an article he’d written titled “Lynching Black People Because They Are Black.” It focused on the violent abuse toward African Americans in Southern states despite full emancipation from slavery. In fact, since 1877, it’s been estimated that some 4,400 African Americans have been lynched with impunity by white mobs.

Now, for what would be his final speech, Douglass was in rare form as he stood up for a law that would make lynching a federal crime. He called lynching “a menace to the peace and security of the people of the whole country” that “threatens to destroy all respect for law and order, not only in the South, but in all parts of our country.”

But it would not be until 1900 that Congress began to take action to outlaw lynching, as every prior attempt failed. Finally, just two years ago, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act was passed, finally making lynching and related acts a federal hate crime. Yes, it appears that it took the U.S. Congress 120 years to catch up to Frederick Douglass.

Nineteen days after his speech, Douglas suffered a fatal heart attack.

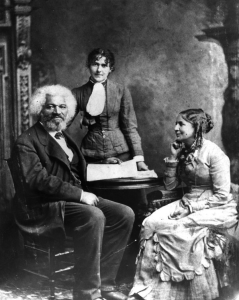

Equal Rights for Women

While Douglass is regarded primarily as an abolitionist, he also strongly supported women’s rights. In 1848, he attended the first women’s rights convention held in the United States. Known as the Seneca Falls Convention, it took place in New York in July 1848 and launched the women’s suffrage movement.

Under the leadership of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the convention discussed 11 resolutions that would give women the same rights as men. All but one passed unanimously — the exception was the ninth resolution, which demanded women should have the right to vote. Many thought that was a step too far.

Fearing that the resolution might fail, Frederick Douglass joined Stanton to give impassioned speeches for passage of the voting resolution. It eventually — and barely — passed. Unfortunately, it would take more than seven decades to pass a national referendum ensuring voting rights for women.

Legacy

Today, the Frederick Douglass Institute at West Chester University maintains the legacy of the great abolitionist and statesman, in part by being an educational and cultural resource that advances multicultural studies. These activities deepen the intellectual heritage of Frederick Douglass while providing a historic anchor for equal rights and social justice.

Through the leadership of WCU, there’s now a Frederick Douglass Institute at each of the 14 campuses of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education. Each is a part of the Frederick Douglass Collaborative, and together they work to advance the intellectual heritage and legacy of Frederick Douglass.

Frederick Douglass Statue at West Chester University

In 2011, the Frederick Douglass Institute began raising funds to create a statue of Douglass. The statue is now situated in a small plaza on the campus, just behind Asplundh Hall at 700 South High Street in West Chester.

Among the first donors was former West Chester mayor, Clifford DeBaptiste, whose family proudly supports the Frederick Douglass Institute. Part of the plan was to have the statue located within a plaza, which was named the Clifford E. and Inez E. DeBaptiste Plaza.

The 10-foot-tall bronze statue of a young Frederick Douglass was created by Richard Blake and dedicated on October 1, 2013 by the Frederick Douglass Institute. It’s now part of a National Historical Landmark recognized by the National Park Service for making “significant contributions to the understanding of the Underground Railroad.”

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer for Arts, Culture and Historic Preservation for the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation. His column raises awareness of Chester County’s rich heritage as we journey to 2026: the year the U.S. celebrates the 250th anniversary of our nation’s independence.

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer for Arts, Culture and Historic Preservation for the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation. His column raises awareness of Chester County’s rich heritage as we journey to 2026: the year the U.S. celebrates the 250th anniversary of our nation’s independence.