Brandywine Stories: Mrs. Denny’s Route to West Chester

In search of freedom and of a woman's name

Housed within a collection of over one million pieces, the newspaper clippings files at the Chester County History Center hold a special allure even among seasoned historians. There are countless stories in this treasure trove.

One distinctive clipping, published on January 1, 1906 in the Daily Local News, told the incredible life story of a woman known only as Mrs. Joseph Denny and her quest for freedom. Before she was Mrs. Joseph Denny, she was known as Mrs. Charles Burns. Though she must have had a name of her own before she married, that mystery would require some digging.

For the staff of the History Center, uncovering her first name was only the start of her story from slavery to freedom.

From Enslavement to Freedom to West Chester

Born into slavery near Culpeper, Virginia, Mrs. Burns spent her days laboring in the fields and her nights mending shirts. Her husband, Charles Burns, was enslaved by another man and lived on a nearby plantation. The couple had three children — Alonzo, Charles and Grace — but the Civil War tore the small family apart when the Confederate Army pressed Charles Burns, Sr., into service driving an ammunition wagon. His wife never saw him again.

The course of Mrs. Burns’s life took an abrupt turn after a routine visit to a flour mill along the Rappahannock River, about 15 miles from the plantation. Instead of the usual miller, she found Union soldiers, including General Geary, who tasked her with delivering an ominous message to her enslaver — “Every foot of ground we trod on belongs to us, with all that is on it.”

Within days, Geary’s forces met the Confederates in battle so close to the plantation that the sound of the cannons was deafening. It was then that Mrs. Burns convinced 25 enslaved men and women to escape with her. She had to make a difficult decision — whether to take her children with her, or leave them behind. Alonzo was 6 years old, while Charles was 4 and Grace was just 2.

With Charles on her shoulders and Grace carried by a cousin, the group left at night and traveled 15 miles on foot to the Rappahannock River, where they found the bridge had been destroyed. Traveling downriver to the very mill where she’d met General Geary, the group found themselves face to face with armed men sent by the plantation to recapture them. In a spectacular show of defiance, Mrs. Burns and her companions refused to return to slavery and dared the men to shoot them.

As the freedom-seeking men, women and children looked down the barrels of Southern shotguns, something entirely unexpected happened — 10 Union cavalry officers appeared on the other side of the river. Realizing the situation, the officers swam their horses across the water and took the four Southerners into custody.

The Union soldiers escorted Mrs. Burns and her companions on foot for four days toward Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Along the way, 130 more freedom seekers joined them on their journey. After receiving word that Confederates were marching to Harpers Ferry to recapture the group, the Union soldiers put them on a train to Philadelphia. The soldiers could escort the group only as far as Baltimore, where they waved goodbye and returned to the front lines.

In Philadelphia, Mrs. Burns was free, but she had three small children and knew no one in the city. While she debated her next move, she met Mrs. John Ingram, who’d traveled to the city to hire farm help. Ingram decided to take Mrs. Burns and the children to her home in Chester County, where the Burns family stayed for six years. During that time, Mrs. Burns met and married Joseph Denny and had two more children with him. When Mrs. Ingram sold her farm, the family followed her into West Chester and made their lives in the borough.

Discovering Mrs. Denny

In 2021, when the History Center’s Anne Skillman came across Mrs. Denny’s story while researching an Underground Railroad walking tour, one thing about the interview rankled her — that the reporter never gave Mrs. Denny’s first name. After digging through the archives, Skillman was able to report that Mrs. Charles Burns/Mrs. Joseph Denny was, in fact, named Judy.

Most Chester Countians know the critical role this region played in the Underground Railroad, but few realize how that role continued all the way up to the very end of the Civil War. If you’d like to read Judy Denny’s firsthand account of her journey to freedom, the full interview is available at the Chester County History Center.

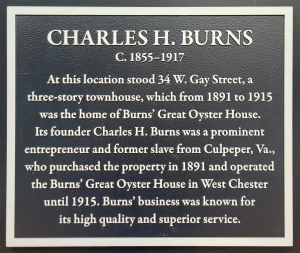

Charles H. Burns

After Judy Denny moved to West Chester, each of her children grew in their own unique way.

Grace, just 2 years old when her mother made her bid for freedom, unfortunately passed away at an early age. Alonzo became a terracotta mason and worked on West Chester’s famous Farmers and Mechanics Building. The middle child, Charles, left the broadest legacy.

Apprenticed as a carpenter, Charles soon shifted his considerable focus to opening his own restaurant. By 1891, he’d raised enough capital to open Burns’ Great Oyster House at 34 West Gay Street (Sedona Taphouse’s current location). He became a leader in local politics and vigorously protested school segregation. An active warrior for civil rights, Burns witnessed firsthand West Chester’s turn-of-the-century descent into policies that echoed the Jim Crow South. After struggling with “tubercular trouble” for years, Burns died in 1917 at the age of 61.

Jennifer Green, Director of Education at the Chester County History Center, wrote this article as part of Chesco250. The Brandywine Stories series is designed to raise awareness of the expansive history and culture of Chester County and build excitement for 2026, the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Jennifer Green, Director of Education at the Chester County History Center, wrote this article as part of Chesco250. The Brandywine Stories series is designed to raise awareness of the expansive history and culture of Chester County and build excitement for 2026, the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.