Brandywine Stories: A Precocious Prodigy

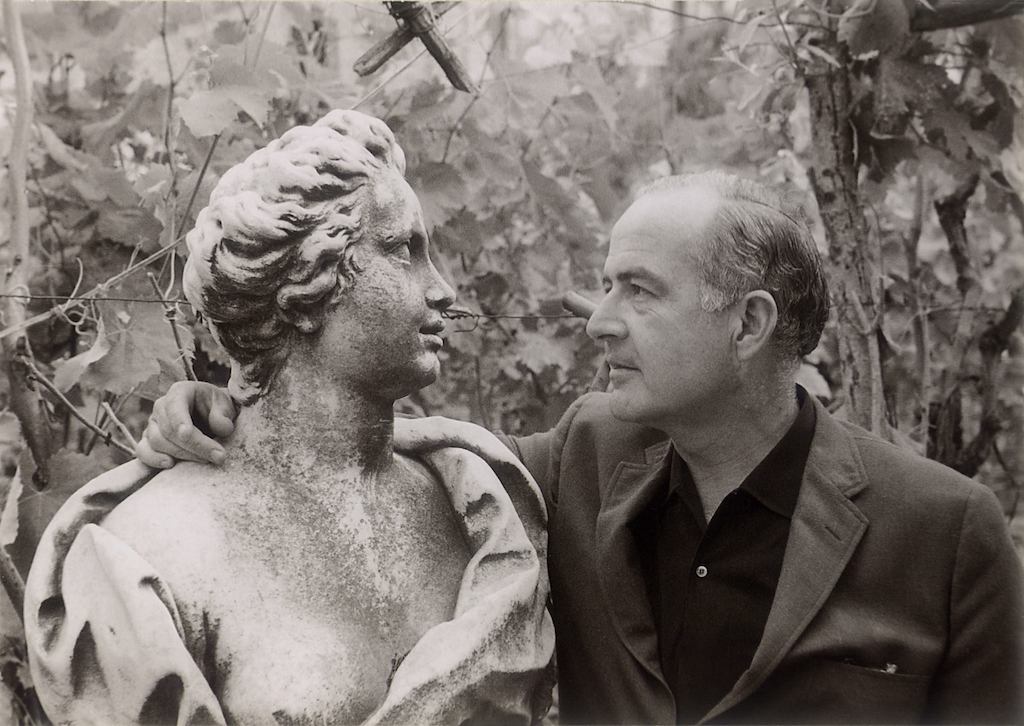

West Chester native Samuel Barber

Stroll the brick sidewalks of downtown West Chester and you may notice an interpretive marker on a building at 35 South High Street. It says simply but proudly, “BARBER BORN 1910.” The marker is meant to recognize the early childhood home of the person many consider to be America’s greatest 20th-century musical composer — Samuel Barber.

Three additional markers can also be found around West Chester — two located at Barber’s next home, at Church and Miner Streets. This plaque describes how his music “went forth to enrich and inspire the world.” A more recent pole banner on East Gay Street refers to Barber as a “child prodigy who grew up to be one of the most celebrated music composers of the 20th century.”

Each is correct. And worth taking in on a stroll.

Early Years

When he was young, Sam Barber, as he was called, developed a precocious natural aptitude for singing, playing the piano and composing music. His family — including his pianist mother and Metropolitan Opera contralto aunt — encouraged his developing musical talent and engaged the best local teachers.

Barber was just 7 years old when he wrote his first original music and age 10 for his first opera. An early performance was covered by the Daily Local News, which gushed about his talent, writing, “the manner in which he executed different selections brought round after round of applause.”

Then, when he was 14, Barber’s parents enrolled the young teen at the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Barber soon found himself in demand for performances within a community of talented musicians. It was there he met Gian Carlo Menotti, with whom he’d form a lifelong personal and professional relationship.

Eventually, as a young man, Barber moved to New York City, where he found a wider range of performers and venues. He soon expanded his composing to include solo instruments, orchestra, opera and voice — he had a rich baritone. But most important, he found a growing audience that appreciated his music. Recognition for his work included two Pulitzer Prizes and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Changing Times

The first half of the 20th century saw dramatic changes in classical music, with experimentation in a world of dissonance versus harmony and cacophony versus melody (think John Cage, Igor Stravinsky). This evolution reflected the challenge for composers to create musical works that sounded new and engaging and not tied to past practices.

Barber rejected, or perhaps ignored, the trends of musical modernism in favor of traditional 19th-century harmonic language. He worked to create musical structures that were lyrical and emotional. Yet after 1940 he did adopt elements of modernism in some compositions, where dissonance and chromaticism became part of his style.

Instead Samuel Barber’s genius was his mastery of melody. With this skill, his music could be tightly woven into a harmonic balance that may have a rich dissonance at times, but still provides a beauty and expression seldom equaled. When the mood moved him, Barber could cross over into other diverse musical styles such as boogie-woogie and the blues — listen to his piece for solo piano, called “Excursions, Opus 20.”

Perhaps the greatest gift of Barber’s music is its ability to partner with other artistic platforms. For instance, his famous “Adagio for Strings” (1936) has been part of numerous film scores (“Platoon,” “Elephant Man”) and played at times of mourning, including the funerals of Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy. Locally, the Brandywine Ballet and Brandywine Singers have used the adagio piece to expand the expressive qualities of both dance and song. These are the types of performances Barber would have encouraged.

Final Days

In 1978, Barber began treatment for cancer, which continued until his death at 70 in 1981. During this time, he continued to write music until his final hours, with the moving “Canzonetta for Oboe and String Orchestra” as his final composition.

Although he lived for several years in New York, Barber always considered West Chester his hometown — he wrote the alma mater for his West Chester high school. He insisted that when he died his funeral should be held at the First Presbyterian Church of West Chester, near his childhood home.

Samuel Barber’s grave is located at Oaklands Cemetery, just outside town, next to a plot purchased for Menotti, who never used it. Instead, a stone inscribed “To the Memory of Two Friends” was erected there.

By the time of Barber’s death, nearly all his compositions had been recorded, ensuring his legacy of expressive, harmonically rich music will endure.

Hear Samuel Barber Live

Nothing compares with hearing music live. Make plans to hear the Kennett Symphony perform Samuel Barber’s lyrical “Violin Concerto” (1940) live, featuring violinist Lun Li, an award-winning violinist from Shanghai. Many consider this piece to be one of the 20th century’s finest string concertos.

Listen for what NPR describes as “a richly expressive opening movement that leads to a razzle-dazzle finale.” Ironically, initial response from friends and supporters was that “there wasn’t enough virtuosity for a concerto” and the “last movement was impossible to play.” But after its premier, it quickly gained a reputation as one of the great American violin concertos.

The program also includes Jessie Montgomery’s “Strum” and Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 8.”

Reserve your tickets for the Sunday, October 12 performance, 3 to 5 p.m. at Uptown! Knauer Performing Arts Center, 226 N. High St., West Chester. KennettSymphony.org. UptownWestChester.org.

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer for Arts, Culture and Historic Preservation for the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation. His column raises awareness of Chester County’s rich heritage as we journey to 2026: the year the U.S. celebrates the 250th anniversary of our nation’s independence.

Malcolm Johnstone is the Community Engagement Officer for Arts, Culture and Historic Preservation for the Cultural Alliance of Chester County, an initiative of the Chester County Community Foundation. His column raises awareness of Chester County’s rich heritage as we journey to 2026: the year the U.S. celebrates the 250th anniversary of our nation’s independence.